Homerton College will be hosting a symposium from 9-11 June to explore how working-class students and academics participate in the University of Cambridge, with the aim of challenging obstacles raised by class differences. The symposium will be convened by Dr David Clifford.

The free, two-day event will look at the obstacles faced at Cambridge by working-class people, both students and academics, how social background may exacerbate difficulties faced by women and people from ethnic minorities, and explore ways of enabling less advantaged students to thrive. It will also celebrate the often unseen working-class origins of many Cambridge academics. The event will consist of seven self-contained discussion panels (see below). Attendees may join as few or as many as they wish. The event will be livestreamed and accessible via Zoom as well as in person. Register here.

David explains:

“The University has faced scrutiny for years over its inclusivity, and has taken very active measures to attract women in STEM, students from lower-income households or under-represented ethnic minority backgrounds, from areas with high levels of deprivation, and to make LGBT students more welcome. Social class is a Cinderella demographic by comparison, despite increasing numbers of first-generation students from less privileged backgrounds arriving at Cambridge. They can feel isolated and unsupported here among their much better supported peers, who may always have expected to achieve highly. Many may never apply in the first place because of how they perceive the University. We now need to tell those students that they are, and will be, included, and that their university teaching staff includes many from backgrounds similar to theirs.”

He continues:

“A significant barrier to entry is a feeling among some sixth-form teachers that their best students should not apply to Cambridge because ‘they will not fit in’ – so they never get to find out either way. Despite recent increases in numbers of state-school and under-represented ethnic minority students at Cambridge – many of whom are also from working class or underprivileged backgrounds – this perception remains.”

David is confident that it’s a reasonable ambition to remove or reduce as many obstacles from applicants’ routes to Cambridge as possible.

He concludes:

“Students from working-class backgrounds won’t *only* be working class after all: they will be female, male, LGBT, ethnic minority, white, well-supported, not supported, and any combination of these and others. If we can challenge the limitations created by social background as well as these other factors, we may attract more excellent students to apply, whatever characteristics they might have. And of course, it isn’t the case that everyone talented *should* want to come to Cambridge. Other excellent universities are available. But if class is an obstacle that puts people off trying, the least we can do is try to remove that obstacle. What they decide in its absence is then up to them.”

Dr David Clifford welcomes academics from across the university to register interest in attending, and in participating as a panel member. Register here.

Discussion panels will include:

- Before we knew we would be academics, and the problems that arose when we were.

- Working-class women academics.

- Support for working-class students at Cambridge.

- Attracting more working-class students to apply in the first place.

- Changing the culture of the University.

- Class barriers faced by ethnic minorities in Cambridge.

- Why are we all changing our accents?

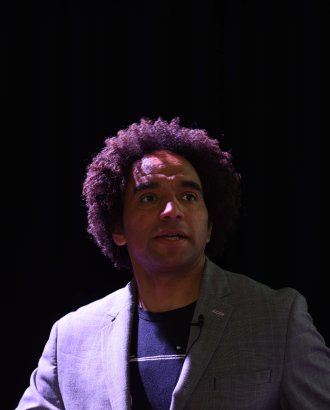

Dr David Clifford is a Homerton Fellow, College Associate Professor, Director of Studies in English, and Tutor. David joined Homerton College as a Fellow in English in 2002. He was a first-generation, comprehensive-educated mature student who achieved his first university place via access courses. Read more about David here or email David here.

Panel 1

Before we knew we’d be academics, and problems that arose when we were.

This panel discusses the experiences academics had when they were undergraduate or graduate students, to give context to the experiences of students today. Questions: did anything change? How were obstacles overcome or reinforced? What is still in place to deter students from applying?

Panel 2

Working class women academics

An all-woman panel to discuss unusual problems faced by women from underprivileged backgrounds both as students and in the academy. A wide range of subject areas should be represented on the panel. Questions: Does being female and working class make a great difference as a student and academic? Were there particular barriers to certain fields, either owing to limits to secondary or sixth form education, or because the fields were overpopulated with privileged males? Do more privileged women academics appreciate these difficulties?

Panel 3

Support for working class students at Cambridge

Student experience can be very isolating if you believe yourself an outsider, even when you are not. To have student participation and perhaps representation on the panel. Questions: Do students think the university is doing enough? What has worked to help them and what is still lacking? How do academics help their working class students?

Panel 4

Attracting more working class students to apply in the first place

One of the ways the perception and culture of elitism at Cambridge is maintained, ironically, is because too few working class students apply in the first place, believing (or being persuaded) that it will not be a place they could flourish. Heads of sixth forms still sometimes discourage their best students from applying on these grounds. We have had dynamic outreach projects in place for some time but if students don’t apply we can’t admit them. Questions: what are we doing to get prospective students to see Cambridge as a place to ground their academic careers? What barriers remain in departments, colleges and among more privileged academic staff that repel students from applying? Are the interviews, our curricula and workload seen as an issue? Why is Cambridge still so predominantly southern? What do students think?

Panel 5

Changing the culture of the University

Building on the discussion in the previous panel, though differently populated I hope. To some extent the perception of Cambridge as elitist is well-founded, and outsiders as well as insiders can see this. It seems likely that those among our colleagues who actually do see the university as better serving a traditional intake will do little to change or may resist changes made by others. Questions: How do we erode the influences of the old school tie, and reactionary attitudes among colleagues who do not share our aims for inclusion? Can we be more proactive in widening participation, beyond the notional ‘targets’ proposed by the Office for Students? Would such measures strengthen the University’s academic standards, or might they carry risks?

Panel 6

Class barriers faced by ethnic minorities at Cambridge

A panel of ethnic minority academics and students. Does coming from an ethnic minority background compound the difficulties when one is also working class? The panel will discuss their experiences of racism, classism, sexism etc, and the sources of these. Specific questions would be adaptations of those from Panel 2.

Panel 7

Why are we all changing our accents?

No other marginalised demographic at university nowadays silently conceals itself from exposure like having a poor or working class background. Moreover, it is probably the only demographic which one grows out of – those of us with working class backgrounds probably can’t make a plausible claim to staying working class in a successful and moderately wealthy middle age. Regional accents soften towards a generic, academic register. Questions: does being a working class student or academic alienate you from the place and people you grew up with? Does class background carry some kind of residual shame that other groups express as pride? Does it matter if we gravitate to middle-class maturity – is this what university offers after all? – or should we do more to preserve the value of working class life and culture?